ARTLYST

Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility is proving to be a profoundly influential as well as innovative book. Its author Ashon T. Crawley – academic and artist – features in two exhibitions (one current, one upcoming) which explore themes taken from the book.

Enunciated Life at California African American Museum takes as its starting point Crawley’s idea that ‘black pneuma’, a communal choreography of inhalation and exhalation experienced within Black Pentecostalism has the power ‘to enunciate life, life that is exorbitant, capacious, and fundamentally social, though it is also life that is structured through and engulfed by brutal violence.’ [1] Otherwise/Revival at Bridge Projects from April utilizes Crawley’s suggestion that the elements of the Black Pentecostal Church—the Hammond organ, emphatic breath, shouting, and glossolalia—create space for ‘otherwise possibility’ or ‘infinite alternatives to what is’ to emerge. Both are group exhibitions featuring artists including Letitia Huckaby, Steffani Jemison, Deana Lawson, Shikeith, Carrie Mae Weems, and Nate Young among others, with Crawley being the only artist included in both.

As referenced by the opening of Otherwise/Revival, Black Pentecostalism began with the Azusa Street Revival. On April 9, 1906, from a home on Bonnie Brae Street in downtown Los Angeles, Rev. William J. Seymour preached a sermon on the spiritual gift of speaking in tongues that would change the course of spiritual history. Once the group moved to premises on Azusa Street, people from diverse races and economic classes congregated to hear Seymour’s sermons—sparking the movement. In the context of Jim Crow segregation, the otherwise possibilities of Black Pentecostalism’s birth included the vision of a racially egalitarian church as well as the exorbitance of speaking in tongues. Crawley writes of Seymour marshalling ‘the power of aesthetic practice in the service of imagining, and living into such imagining, otherwise possibilities’ and of wanting ‘to create an alternative mode of existence that would disrupt the here and now of his inhabitation.’ [2]

In terms of the Arts, Black Pentecostalism is known primarily for its music and the many musicians who have come from the church. However, the visual arts have also found expression within the movement; this being another example of otherwise possibilities, particularly when contrasted with the approach to the visual arts found elsewhere within Protestantism. Kymberley N. Pinder provides a series of informed case studies in Painting the Gospel: Black Public Art and Religion in Chicago from differing stages of the movement to demonstrate the way such art has carved out celebratory heterotopias demonstrating that alternate relations can be established. By ‘deploying the basic principles of Black Liberation Theology, consciously or not, these artists have created biblical images that mirror the faces of their African American audiences’ ‘internalizing the equation “divinity equals blackness,” which transforms their “nobodiness” into “somebodiness”.’ [3] In Otherwise/Revival, this heritage is highlighted primarily through works by Clementine Hunter and Sister Gertrude Morgan.

However, these are primarily exhibitions that visualize the impact of the historic Black church— specifically the Black Pentecostal movement—on contemporary artists. Those featuring in Enunciated Life draw upon cathartic bodily expressions found in Black spirituality, such as emphatic breath, shouting, and glossolalia.

In Transmedia Prayer: Hymnal, Billy Mark creates an embodied hymnal of movement phrases, melodies, and text presented on three screens. Along with members of his community, he performs a series of gestures and sounds inspired by verses from the book of Isaiah that relate to selflessness, generosity, and communion. Viewers are invited to wave their hands or move their bodies in front of the sensors displayed beneath each of the monitors. Movement in front of the sensor prompts an offering of sound, text, or audio on each of the three screens. Mark writes that ‘It is from our bodies that these words of life and melodies of the unknown break loose’ and so, in this work, ‘we invite the body, the voice, and our words into a moment of mutual self-giving.’

In I. MELISMATA (2020), Tiona Nekkia McClodden has separated vocals from music in over sixty gospel songs to isolate the melismata, the runs which have their roots in religious chants but are more popularly associated with gospel and R&B virtuosity. Melismatic singing is when multiple notes are sung to a single syllable of text. This collection of vocals was then arranged in a long-form continuous vocal run. The recordings come from the early twentieth century to the present, recalling the artist’s experience of finding sanctuary during her childhood in listening to gospel cassette tapes on her personal Sony Walkman stereo player. Runs can be improvisational, altering course midway through the riff, and so they align with many of the expressive movements and sound-based gestures in the Black church that are spontaneous, unplanned, and distinct. In this way, the work invokes the fugitivity and ephemerality of this particular singing style.

In Ashon T. Crawley’s two dancing in one spot works, the artist re-enacts the ‘praise break’—a moment during church worship when the congregation is encouraged to dance and testify their faith through their bodies—to create the works. Crawley wants to ‘make things through shouting, through clapping, through getting my flesh messy in order to attempt something of the feeling of spirit I’d have when I was in the Blackpentecostal churches that formed me.’ [4] For these works, he shouts and whoops to praise music whilst dancing on pigment powder and acrylic paint scattered on paper and ground by his feet into abstract forms. In this way, Crawley impresses upon paper all the possible routes of praise and joy that made each impression.

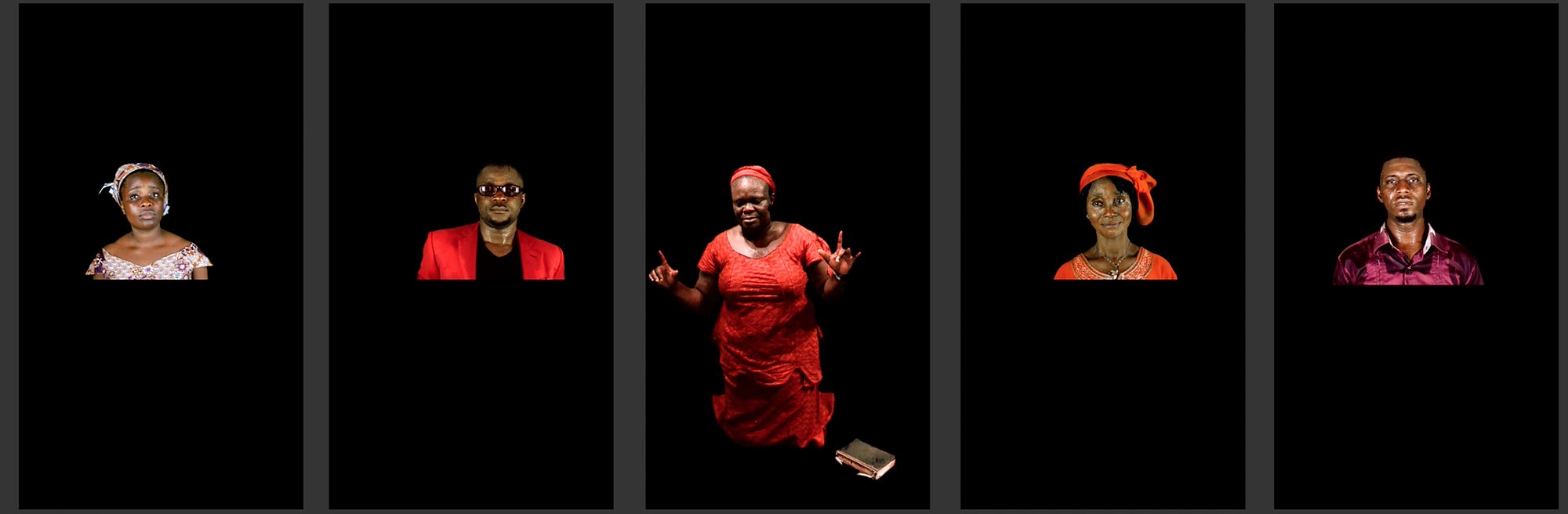

Although not all the artists in Otherwise/Revival grew up in the Black Pentecostal Church –some have Catholic backgrounds or grew up in other denominations or did not grow up in a religious environment of any kind—each were invited to participate because their work embodies the spirit of revival. In Zina Saro-Wiwa’s immersive video installation, Prayer Warriors: The Survival Performances, five Evangelical pastors call out to Jesus for a miracle in the Niger Delta, a landscape undergoing trauma. Praying in Ogoni—the language of the Niger Delta region—as well as in tongues and in English, the pastors begin to move, their gestures and passion reminiscent of the act of tarrying in the Black Pentecostal Church, a simultaneous summoning and waiting upon the Lord for change. Their cries of lamentation and shouts of joy reverberating in a liminal space pose the question: Can enacting a performance of emotion transform hearts and minds?

McArthur Binion is ‘looking for something that’s beyond language.’ In 2020, he began work on a project of minimalist altarpieces in Italy. This project expresses a desire to ground the transcendence of his grid in the viscera of his being a Black artist in America. Photocopied pages from address books, birth certificates, and images of the artist’s hand—the geography of his life, which becomes the under-conscious of the work—create a meaning-full texture. The grid holds it all together so that, in the series healing: work, deep blue and red curves push up against silvery grey and golden-hued backgrounds creating an unspoken text where language—and prayer—might emerge.

The artistic practice of Genesis Tramaine is entirely spirit-led as her portraits draw to the surface the inner working of the Spirit in the lives of those she portrays. These portraits are not based on external representation but on creating an equivalence to the interior spirit of her characters, with the paintings remaining incomplete until the spirit in her has spoken to the spirit in the portrait. The girl in Last to Get My Hair Done is the artist herself. In her statement about the piece, she wrote, ‘When I was a little girl, I had to, ’get our hair done’ on Sunday morning or Saturday evening for church and the week ahead. I absolutely hated being last when I was a young girl. But I’ve learned from the Word that it’s not so bad … the Word says and the last shall be served first and the first last. Matthew 20.’ Scripture, memory, and faith comprise the blueprint for a place in which ‘otherwise possibilities’ and revival can be made manifest.

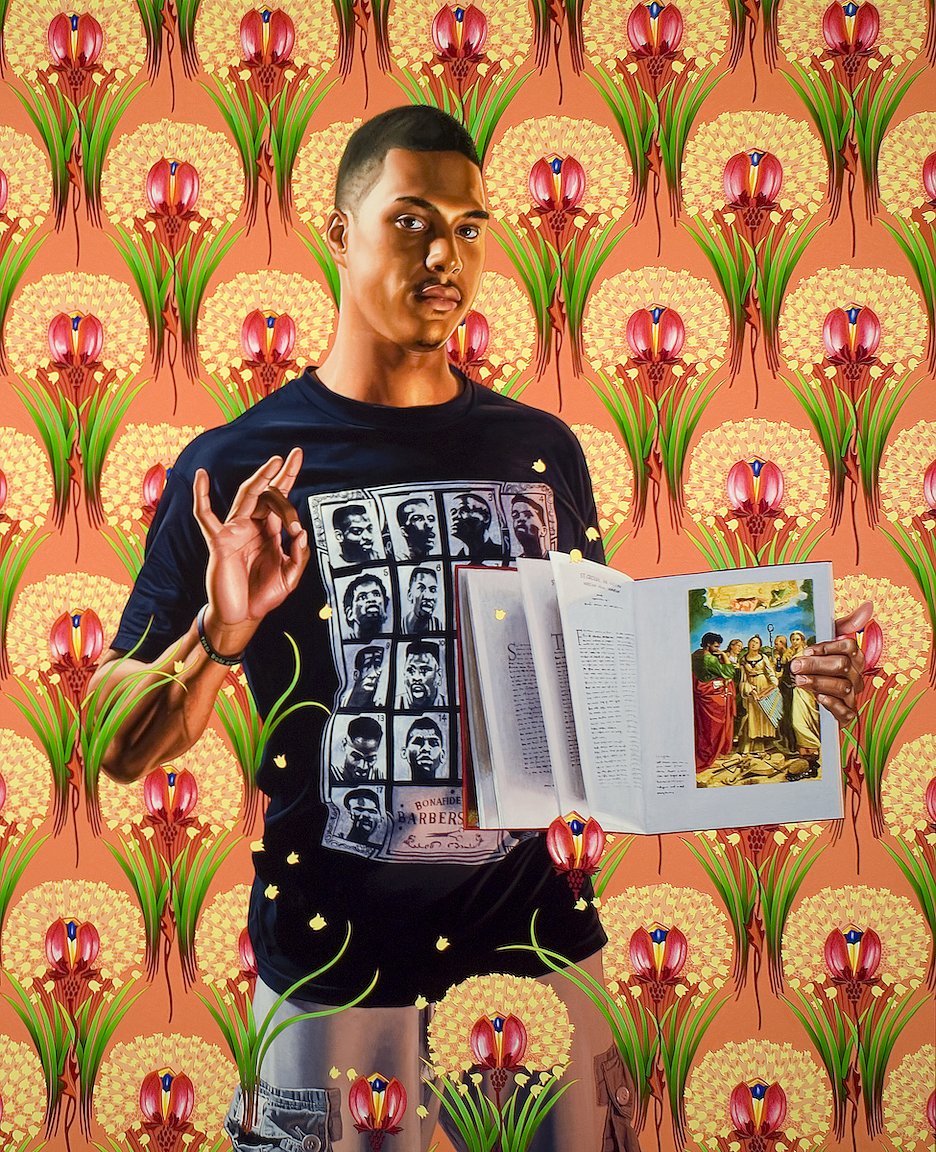

In the painting St. Nicholas of Myra, Kehinde Wiley reimagines the traditional Catholic Saint Nicholas, patron saint of miracles and the working class, as a contemporary Black man. Wiley’s portraits draw attention to the absence of African Americans from historical and cultural narratives by using the conventions of traditional European portraiture while replacing saints and aristocrats with his colourful paintings of African Americans. Victoria Emily Jones has noted that by ‘translating European devotional paintings—fashioned in the image of the white ruling class—into a contemporary idiom that places black bodies up front and center, Wiley rectifies the lack of representation of racial minorities in and as the body of Christ.’ [5] Wiley rewrites a history where Black men can be both subjects and saints while simultaneously being themselves.

Creating ‘otherwise possibilities’ is a way of rewriting Black Pentecostalism, which, as Crawley has experienced, comes with ‘proclivities for classism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia.’ His belief and that of these exhibitions are that ‘the resource for critiquing the ways sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and classism inform the world exist within the world itself, the breakdown and critical analysis is an otherwise possibility full in its plurality and plentitude already within the world.’ [6]

That plenitude and plurality is found in these collections of artworks composed of worship, lament, joy, word, breath, community, and improvisation, with every piece—sculptures, paintings, video, and performances—emphatically celebrating the significance of music, praise, breath, and community. As the exhibited artists reflect on their traditions, heritages, passions, and talents, they remind us of the dramatic architecture and specific gestures that make clear sensations of desire, longing, faith, and vulnerability. Their works help us explore the innermost emotions that are shared through religion, aiding the prospect of surrender and ecstatic freedom and cultivating spaces where art thrives and expresses a unifying language for all.

Their alternative or ‘otherwise’ modes of existence can serve as disruptions against the marginalization of and violence against minoritarian lifeworlds and possibilities for flourishing. In their work, as in the words of Crawley, protest and prayer are fused:

‘Otherwise is the practice of breath and breathing. To breathe in an inhospitable place, in the context of settler colonialism and antiblack violence. To breathe inhospitable air and atmospheres. To breathe for black life, blackqueer possibility, is protest, is prayer.’ [7]

[1] Ashon T. Crawley, Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017), 38.

[2] Ashon T. Crawley, Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017), 15.

[3] Kymberley N. Pinder, Painting the Gospel: Black Public Art and Religion in Chicago (University of Illinois Press, 2016), 15 & 23-24.

[4] ‘Lonely Letters: A conversation between Ashon Crawley and Elleza Kelley’ by Elleza Kelley and Ashon T. Crawley June 15, 2020, The New Inquiry, https://thenewinquiry.com/lonelyletters/

[5] ‘Christian-themed portraits by Kehinde Wiley’ by Victoria Emily Jones, August 31, 2016, Art & Theology, https://artandtheology.org/2016/08/31/christian-themed-portraits-by-kehinde-wiley/

[6] Ashon T. Crawley, Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017), 36.

[7] ‘Protest, Prayer’ by Ashon Crawley, Dialogues: Blog of the American Studies Journal, July 8, 2020, https://amsj.blog/2020/07/08/protest-prayer/